Celebrating Black Contribution to The Car World in Black History Month

Next time you look up at a three-signal traffic light, take a moment to give thanks to one Garrett Morgan who saved us from calamitous collisions at junctions, by registering a patent for a three-signal traffic light back in 1922.

Garrett was an African-American inventor and businessman whose other inventions included a smoke hood (the predecessor to the gas mask) and hair care products. But he is not the only black person to have left a significant and lasting legacy in the world of automotive. An industry that often overlooks contributions from minority communities.

Fred Patterson could have been Henry Ford

Henry Ford is rightly regarded as the progenitor of the mass-produced car, famously with the Model T. However, Frederick Douglas Patterson (already the first African-American to play in the Ohio State University football team in 1891) set a further precedent when he turned his dad’s carriage-making company into a car manufacturer.

The Greenfield-Patterson automobile was produced in 1915. As many as 150 were made for sale at a price of $850, incidentally about the same as a Model T introduced a few years earlier. Had he secured the financing he sought to rival Ford, we might be driving Greenfield cars around today. Eventually he moved to making lorries and buses until the business closed in 1939.

Black car designers

McKinley Thompson Jr is regarded as the first African-American car designer having worked on the original Ford Bronco, Thunderbird and concepts for the Mustang and GT40 race car. He remembers seeing a 1934 DeSoto Airflow as a 12-year-old on the streets of New York and deciding then and there he wanted to be a car designer.

Having served as an engineer during World War II, on his return he won a car design contest for Motor Trend magazine and earned a Ford scholarship. Alongside a successful career for the car giant, he even designed the Warrior concept – a cheap plastic-bodied car designed for Africa and developing countries. It never went into production, but still lives in Ford’s collection of classics.

Then there was David Gittens, an artist, inventor and philosopher, who left the States and moved to England in the mid-60s after working as a photographer for Car and Driver magazine. Gittens soon started designing and making concept vehicles including a gas-powered single seat city car, an electric city car, a three-wheeler, an expandable six-wheeler and most famously the Ikenga GT supercar that even appeared on BBC’s Blue Peter.

Powered by a Chevrolet V8 engine mounted midship and powering the rear wheels, it had a five-speed manual and was based on a McLaren M1B platform. It featured such futuristic concepts as an on-board computer and cameras. Named after an ancestral spirit of the Igbo culture in Nigeria, it is still thought to exist though its whereabouts is unknown.

More recently the highest-ranking black person in the automotive industry was Edward Welburn (now retired) who was General Motors' Vice President of Global Design from 2003-16. Falling in love with a Cadillac show car at the Philadelphia Auto Show as an 11-year-old, he wrote to GM asking to be a car designer. Some years later, in 1977, he was granted an internship with the company and spent his entire 44-year career there, overseeing the development of cars like the Chevrolet Corvette and Camaro and the Cadillac Escalade.

Black racing drivers

Sir Lewis Hamilton is the most successful black racing driver in Formula 1, and has already made his mark with a remarkable record-equalling seven world championships, but he wasn’t the first professional black racing driver to get into an F1 car.

William Theodore Ribbs Jr tested a Formula 1 car in 1986 with the Brabham team. He never raced in F1 but did qualify for Indy 500 in 1991 and also competed in the Trans-Am series, Champ Car, NASCAR, even a truck-racing series.

Going back to the early days of motor racing in America, Charlie Wiggins was a World War I mechanic eventually moving to Indianapolis and opening a garage. His dream was to race in the Indy 500 and he even built a race car from salvaged junkyard parts, however he could not enter the famous race as black people were barred from mainstream motor sports events at the time.

Undeterred he and others created the Gold and Glory Sweepstakes, a black-only 100-mile race over a mile-long dirt track in Indiana State Fairgrounds. He won three championships, eventually losing his leg in a crash in 1936. That didn’t stop him, he made himself a prosthetic leg and continued to build racing cars into the 1970s. By which time, he did get to see a black driver race at Indianapolis.

World War II veteran Wendell Scott had frequent run-ins with the police for speeding. Ironically, when organisers of a local stockcar race series decided, as something of a gimmick, to recruit a black driver for a one-time race, it was the cops that recommended Scott!

He did better than expected. In fact, he created history by eventually becoming the first licensed African-American NASCAR driver racing in the top division from 1961 to the early 70s. There’s even a biopic on his exploits starring Richard Pryor titled ‘Greased Lightning’ and released in 1977.

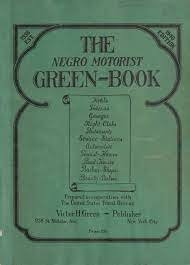

The Green Book

In 1930s America, an emerging black middle class found travelling by road fraught with difficulties and dangers during the era of the Jim Crow laws that legally sanctioned humiliating segregation and discrimination.

A New York City postman, Victor Hugo Green took it upon himself to write a book that would help his fellow black motorists. ‘The Green Book’ (first published in 1936) became an invaluable resource advising on places to avoid, as well as where to eat and find welcoming accommodation.

Made famous by a 2018 movie of the same name, it could be argued that the Green Book was as much a tool of segregation as the discriminatory laws themselves, but it represented the efforts of Victor Green to help his community to travel in safety. Shortly after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 which banned discrimination, the Green Book was no longer needed and went out of publication.